So far, only a few places outside of Earth have been thought of as containing life; Mars, and some icy moons of giant planets, including Europa and Enceladus. However, on September 14th, scientists revealed a shocking discovery to the public. They made a discovery that suggested existence of extraterrestrial life on Venus, one of the planets least likely to be habitable and hence overlooked by astronomers, in the form of a toxic gas called phosphine.

For decades, astronomers have steered all their attention towards Mars, crowding it with probes and rovers in hopes of finding any traces of life. Due to its similarities with Earth, habitable conditions and presence of water in the past, it has always been the subject of interest for NASA, ESA, and other space agencies. Venus, on the other hand, was being accompanied only by the Japanese probe Akatsuki launched in 2010, and has not been given much attention.

But the discovery of phosphine has changed all that. This discovery seems to be a promising sign of life until proven otherwise. Now that Venus has gained the attention of astronomers and scientists, it will have to entertain a few guests pretty soon.

Contents

What Is Phosphine And How Does It Indicate Presence of Extra-terrestrial Life on Venus?

Phosphine (PH3), or hydrogen phosphide, is a colorless, flammable, and extremely toxic gas. It consists of one phosphorus and two hydrogen atoms in a pyramid-like structure.

It is important to note that the presence of phosphine is not proof of life on Venus, but merely a hypothesis. At the moment, life is the only plausible explanation for the mysterious formation of phosphine, but it could also be caused by a chemical reaction not yet known to scientists. “Now that we’ve found phosphine, we need to understand whether it’s true that it’s an indicator of life,” says Leonardo Testi, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory in Garching.

Here on Earth, phosphine is formed in two ways; naturally by microorganisms, or manufactured artificially in labs. It is found in the intestines of some animals, badger and penguin feces, and is produced in environments containing anaerobic life.

Despite knowing phosphine is found where anaerobic life lives, scientists have yet to figure out how that actually happens. “There’s not a lot of understanding of where it’s coming from, how it forms, things like that.” said Matthew Pasek , a researcher and associate professor at the University of South Florida in Tampa who specializes in astrobiology, geochemistry, and cosmochemistry. “We’ve seen it associated with where microbes are at, but we have not seen a microbe do it, which is a subtle difference, but an important one.”

Phosphine had been used as a weapon during World War I, and is still in use by some terrorist groups, due to its toxicity. It is also used for fumigation on farms and as semiconductors.

On Jupiter and Saturn, though there is no extraterrestrial life, it is produced as a result of extreme conditions. The conditions on those planets are just right for forcing hydrogen and phosphorus atoms together to form phosphine.

If we already know phosphine exists on Jupiter and Saturn, then how come it’s surprising that it was found on Venus too? The conditions found on Venus are not suitable for the natural formation of phosphine. On the giant planets, the pressure and temperature near their cores are extreme enough to produce phosphine and let it out in the atmosphere. That’s not the case in Venus, which is too rocky for natural phosphine formation.

The phosphine detected on Venus existed within the clouds of sulfuric acid; therefore any phosphine that makes it up there would be eradicated by the ultraviolet radiation. Therefore, there must be a source of phosphine on the planet which continuously produces this gas, which would explain how it keeps replenishing in the atmosphere. William Bains, a biochemist at M.I.T., also mentioned this fact, “The light is constantly breaking the phosphine down, so you have to continuously replenish it.”

Scientists already know that microbes can be found in cloud particles. However, as clouds are fleeting here on Earth, they cannot make their ecosystems there. But on Venus, the clouds persist for millions of years. “On Venus, that puddle never dries up” said David Grinspoon from the Planetary Science Institute. “The clouds are continuous and thick and globe-spanning.”

Why Is This Discovery Such A Big Deal?

Scientists have been scouring Earth’s neighborhood for a planet capable of accommodating life, but in vain. Due to the conditions in Venus, it was checked off as a possibility.

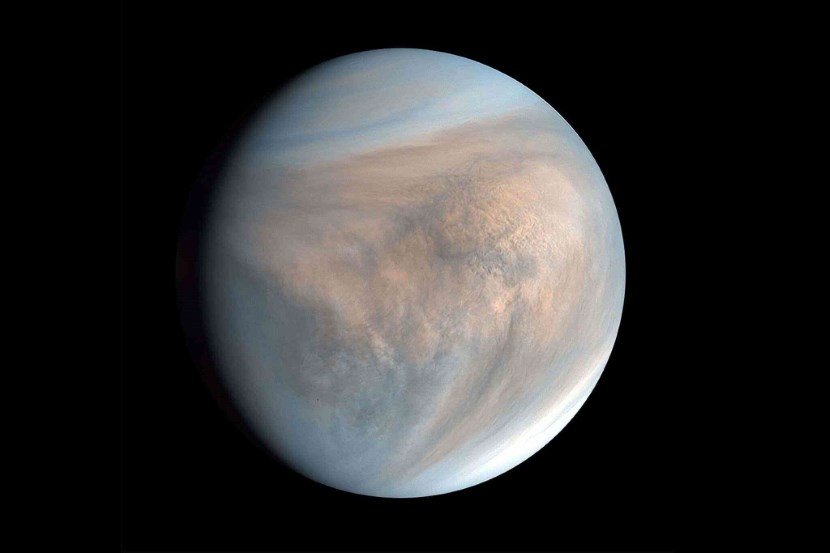

Named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty, Venus is the brightest object in the night sky, after the moon, and can be seen on a clear night as a sparkling white dot. This brightness is not only due to its short distance from Earth, but also due to its unique atmosphere that can reflect sunlight.

The temperature on Venus can reach 900° Fahrenheit, which is over 480° Celsius, hot enough to devour any spacecraft attempting to land, and definitely too hot for life as we know it. The pressure there is around 1,300 pounds per square inch, which is 90 times the atmospheric pressure on Earth and equal to the pressure 3000 feet under Earth’s ocean.

The Venusian atmosphere is mainly packed with carbon dioxide and corrosive sulfuric acid clouds.

The surface conditions of Venus make it impossible for life to exist there, but it’s different when it comes to Venus’s skies. The temperature and pressure at the upper atmosphere, where phosphine was detected, is almost the same as that of Earth, making it the area in the Solar System that most resembles Earth’s environment. Although sulfuric acid is found in that layer, the microbes found on Earth also seem to thrive in corrosive environments such as hot springs and volcanic fields.

What Led To This Discovery?

It all started when Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University, read about how phosphine could act as a biosignature for Earth if seen from space, far away. “I was really fascinated by the macabre nature of phosphine on Earth,” she says. “It’s a killing machine … and almost a romantic biosignature because it was a sign of death.”

Knowing that Venus resembles Earth in its size and mass, she wanted to test this out on it as well, so she used the James Clerk Maxwell telescope from its perch atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

In a few hours, she found traces of phosphine gas. “I wasn’t really expecting that we’d detect anything,” Greaves told The Atlantic.

To find out more about this bizarre discovery, Greaves reached out to Clara Sousa-Silva, a researcher and molecular astrophysicist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who spent her career studying phosphine and was the one who identified it as a biosignature. In 2019, the two of them, along with their colleagues in Chile, used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, a much more sensitive array of telescopes, to confirm the presence of phosphine. Using the ALMA, which could detect the energy absorbed and released by spinning phosphine molecules, they again picked up phosphine, this time in much larger numbers. They calculated a concentration of 20 parts per billion. This may seem like a small number, but it’s actually thousands of times greater than the small amount of phosphine found in Earth’s atmosphere, which is a few parts per trillion.

“I immediately freaked out, of course. I presumed it was a mistake, but I very much wanted it to not be a mistake.” Sousa-Silva said.

They were also able to pinpoint the location of the gas, found at an altitude between 32 and 37 miles, where the temperature and pressure aren’t as harsh as the surface.

On the confirmation of the presence of phosphine, Sousa-Silva and other researchers spent a year using computer simulations to imitate the Venusian atmosphere in order to rule out its other possible sources. They tested the chemical reactions of gases with each other, droplets of sulfuric acid, or with rocks present on its surface. They also studied volcanoes, lightning, meteorites, and earthquakes; anything that would provide an outcome.

They found that there was a chance volcanic activities and lightning could release phosphine, but not in abundance, and certainly not enough to replenish it in the atmosphere. Ultimately, life seems like the only known source that could produce phosphine in such a large amount.

Hints Of Life On Venus From Previous Years

Surprisingly, phosphine is not the first discovery that points towards extraterrestrial life on Venus; rather it’s the most convincing. Previous speculations were only less likely to be proven true as there were other possible explanations for them besides life.

One of the signs suggesting life on Venus includes the presence of methane in the skies of Venus. The Sun’s radiations continuously break down methane, so there must be a source keeping it in the atmosphere. However, life is not the only possible explanation for this. Methane can be produced in Venus by simple chemical reactions; hence the theory of the presence of life was overruled.

In a 1967 paper, astronomer Carl Sagan and biophysicist Harold Morowitz explored the possibility of life in the clouds of Venus. They suggested that even though the surface of Venus may not be able to support life, its skies might.

Somewhere in the timeline of the universe, Venus was just as habitable as the seas in present-day Earth, covered with carpets of oceans containing life. Over the course of the past billion years, the surplus of greenhouse gases in its atmosphere transformed it into the ball of fire it is today. It can be assumed that as the oceans evaporated, the organisms on its surface may have escaped into the skies to adapt. Penelope Boston, a NASA astrobiologist, says, “Any life there now is much more likely to be a relic of a more dominating early biosphere. I think it’s a blasted hellhole now, so how much of that ancient signal could have held up?”

Some early observations also revealed an intriguing fact about Venus; some parts of its atmosphere absorbed more ultraviolet lights than expected, resulting in black streaks in its atmosphere. There could be a few reasons for this. A NASA astrobiology article states “It could be particulate matter mixed into the clouds, or a substance that has been dissolved by the droplets of sulfuric acid, or perhaps crystalline in nature, like ice. Iron chloride has been proposed, but there is no confirmed mechanism that could loft particles of iron chloride 50 to 60 kilometers above the surface, particularly as winds near the surface only blow weakly through the dense lower atmosphere.”

Although nothing in our knowledge can factually explain these discoveries, the existence of extraterrestrial life remains a plausible theory. We don’t even know if any possible life even remotely resembles life here on Earth, but that’s all we can imagine. “When looking for life elsewhere, it’s so hard to not be Earth-centric,” Dr. Sousa-Silva said. “Because we only have that one data point.”

What’s Going To Happen Next?

All we know right now is that there is a significant amount of phosphine present in the Venusian atmosphere that previously wasn’t there. But this information isn’t even remotely enough to draw a conclusion on the existence of life in Venus. Now, scientists will have to conduct immaculate observations and missions to gather as much information as they can.

Observations

Astronomers will now take the research further by conducting a number of observations using different telescopes. “We are proposing to use two instruments.” says Jason Dittmann, an exoplanetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He plans to oversee these observations with Sousa-Silva using the two mentioned instruments; One located at the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii, and the other on NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, which is an airborne observatory designed for infrared astronomy observations in the stratosphere.

These observations are necessary to provide another, more authentic verification of phosphine, and more specific information related to it, such as its precise location and variation in concentration levels.

Dittman’s team had intended to carry out these observations in July 2020 but had to postpone them due to the coronavirus outbreak. However, Dittmann affirmed, “We’re hopeful we’ll start getting data in the near future.”

Space Missions to Venus

To know for sure what exactly is going on inside Venus, we can’t rely on observations from Earth. We need to dive into Venus’s atmosphere, where no spacecraft has travelled for more than 35 years. Since the Soviet Vega probe Venera 13‘s mission in 1982, which lasted two hours on the surface of the planet, no other spacecraft has landed on Venus.

With this new discovery, astronomers have busied themselves into planning their visits to Venus. “This discovery is now putting Venus into the realm of a perhaps inhabited world,” says Martha Gilmore, a planetary geologist at Wesleyan University who has proposed a mission to study Venus in-depth and search for signs of past habitability. “It’s always been important for Venus science; it is getting increasingly important and perhaps accessible and a little bit better understood,” Gilmore said. “If we’re going to tackle a problem like this, a flagship could do that.”

There is only one spacecraft assigned to Venus, the previously mentioned Japanese probe, Akatsuki. Akatsuki has been circling around Venus’s orbit for half a decade, and now it can help out with another mission.

Although its instruments are not fit for phosphine detection, it can still play an important role. “The atmosphere and the clouds are the platforms for life,” says project scientist Takehiko Satoh, a planetary scientist at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency in Sagamihara. “We can provide information about that.”

Currently, there are three other spacecraft occupied in their respective missions. These three spacecraft will reroute to Venus. Although their equipment is not suitable for the detection of phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere, as they were designed for different purposes, they might be able to assist in other ways.

One of them is Europe and Japan’s BepiColombo spacecraft, which made its way to Mercury on October 20, 2018, for its 7-year mission. There’s a chance BepiColmbo will be able to pick up phosphine next using its infrared instrument.

There are also two spacecrafts sent to the Sun, which are the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter and NASA’s Parker Solar Probe. The Parker Solar Probe is also equipped with an instrument for studying solar particles, which might help in the detection of phosphine.

“It is a low probability, but I would not completely rule it out,” says Nour Raouafi, an astrophysicist and Principal Professional Staff at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. He is also the project scientist of the Parker Solar Probe Mission.

What Could Possible Future Missions To Investigate Life On Venus Look Like?

Before astronomers rush to send special spacecraft over to Venus, they must study the presence of phosphine as much as they can on Earth. Several scientists, including Matthew Pasek, are unconvinced. They believe merely by knowing there is phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere, we cannot deduce that it points towards extraterrestrial life instead of just an undiscovered chemical process. He says, “Modelling is a reasonable response right now. Most chemistry that we think of for Earth is dominated by water. On Venus, that’s not the case. So there’s a lot of experiments that no one has done.” He believes the existence of life on Venus is possible, but he doubts that’s really the case. Sousa-Silva also has similar views. “I’m skeptical,” she said. “I hope that the whole scientific community is just as skeptical, and I invite them to come and prove me wrong because we’re at the end of our expertise.”

In case of earthly observations proving to be successful, scientists are hard at work to plan out future missions to Venus to confirm whether their speculations about extraterrestrial life are true. Several organizations are considering sending their aircraft to these missions. A member of the BepiColombo team at the German Aerospace Centre, Jörn Helbert, stated that the discovery strengthens the case for such missions.

Shukrayaan-1

An Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) aircraft, called Shukrayaan-1, was initially set to launch in 2025 to study the Venusian atmosphere. Although the ISRO has not yet commented on whether they would contribute, Sanjay Limaye, a planetary scientist at the University of Wisconsin, believes, “They would be mistaken if they don’t see that opportunity.” He says the ISRO has enough time to reconsider its instruments as well.

VERITAS

VERITAS, or Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy, is a mission concept proposed by NASA. Its aim is to determine its activity, research about its past and present, compare it with Earth, and produce 3D and high-quality topography of the planet.

Despite the similarities Venus shares with Earth, it seems to be so much more different, with its hellish atmosphere and acidic clouds. VERITAS’s goal is to study what led to these differences.

Suzanne Smrekar, the principal investigator of VERITAS, says, “VERITAS has hundreds of kilograms of excess launch mass that NASA could choose to use for auxiliary small spacecraft designed for that purpose.”

Although VERITAS wouldn’t directly examine the atmosphere of Venus or confirm the detection of phosphine, it can help with its own capabilities. According to its design, it would gather information about the surface of Venus. “To get the first look at global composition at least is going to tell us so much, even if the method is not everything you might wish for,” Smrekar told Space.com. “It’s going to be, I think, really spectacular in terms of enhancing our understanding of surface chemistry.”

EnVision

EnVision is an orbital mission to Venus proposed by The European Space Agency, which would launch in 2032. This geology orbiter could suggest alternative sources for phosphine, if any, such as any active volcanoes. It would be capable of detecting centimeter-scale changes on the surface of the planet which would help it determine volcanic and tectonic activity, as well as rates of weathering and surface alteration.

DaVinci+

Even NASA, which hasn’t sent a spacecraft to Venus in the past 30 years and declined funding, will now fund two of the four finalists for the agency’s next two $500 million planetary missions under the NASA Discovery Program, as it announced in February .

One of those finalists is DAVINCI+, (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) a small mission for studying the deep atmosphere of Venus. It would measure the noble gases in the planet, search for sulfuric acid and carbon near the surface in case of recent volcanic activity, and map the planet’s geology and highlands.

So, Is There Life On Venus?

For now, there is no knowing what the facts are until we gather some data to support it. “Maybe Earth and Venus are two different paths that habitable planets can take in their evolution,” says Jörn Helbert, who is also part of VERITAS. “To answer that, we need to get the fundamental data sets for Venus that we have for Mars and even Mercury.”

“For the last two decades, we keep making new discoveries that collectively imply a significant increase of the likelihood to find life elsewhere,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, the Associate Administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “Many scientists would not have guessed that Venus would be a significant part of this discussion. But, just like an increasing number of planetary bodies, Venus is proving to be an exciting place of discovery.”

Now, all there’s left to do is wait until experts gather enough information to be able to confirm the presence of life. “Venus is such a complex, amazing system, and we don’t understand it. And it’s another Earth. It probably had an ocean for billions of years, and it’s right there. It’s just a matter of going,” said Martha Gilmore. “We have the technology right now to go into the atmosphere of Venus. It can be done.”

The universe holds a vast amount of possibilities way beyond our imaginations, so finding extraterrestrial life, even if it’s on a planet like Venus, is not unimaginable. And only science can prove otherwise.